Rigor & Joy Are Not In Opposition: Notes On a Week of School Visits In California

Solvit Founder Melissa Groff makes friends with a redwood.

When Melissa Groff – current Head and co-founder of Solvit Academy – and I began imagining the next chapter of the K-6th educational experience, our conversations overflowed with ideas and energy. Certain school names surfaced again and again — schools with which we felt a kinship, a shared vision, and an aligned pedagogical orientation. Eventually, our design conversations reached a depth that demanded more than research from a distance. We decided to fly to California.

We were eager to see what decades of progressive educational work and a community of non-conventional thinkers looked like in 2026. I worried, a little, that the schools we visited might be innovative in writing but more traditional in practice — the pressure to do things "as they've always been done" is strong, and never more so than in schools right now. What I knew in my heart was that student-centered teaching and learning, the cultivation of independent problem-solvers, and the practice of living with fearless imagination were right for children.

I know that students in non-conventional models still learn their multiplication and division, still learn experimental design, still learn how to write and read — but they also learn how to be intentionally curious, how to use their voice, how to invent and imagine, and how to discuss and defend ideas with compassion and empathy.

Still, I needed to confirm that what I wanted for elementary-aged students in Lancaster — including my own children — was working somewhere else.

We first visited the Lower School at Hillbrook School, a beautiful, evergreen campus with an outdoor stage and amphitheater. Hillbrook's founding name was "The Children's Country School," and that DNA is still very much visible. A creek — the site of many science lessons — runs through campus, and students spend much of their day moving between buildings outdoors. We walked past "The Village of Friendly Relations" (child-sized and child-built structures that once functioned as real businesses serving local townspeople, including a bank) and into The Hub, and that was the moment I knew we were with our people.

Here is what I mean by that: progressive education is not one single thing, and it is not any one aesthetic.

Progressive education means designing with students in mind — being responsive to who they are right now, the world they currently inhabit, and the worlds they will enter when they are no longer in our care. Though part of Hillbrook's campus has the warm, unhurried feel of a summer camp from the 1960s, The Hub will remind you that you are very much in the 21st century, mentoring designers, leaders, and innovators. We believe that learning from and in the natural world is essential to a young person's development — and we also believe that students deserve the chance to investigate real-world scientific problems, design meaningful solutions, and grapple seriously with the ethics of technology. It matters enormously that young people discover what they care about early. Connecting to work that matters is not a luxury reserved for adults.

At Stone, we are building a curriculum that makes that connection possible from the very beginning — one that hones individual interests, demands genuine imagination, and grows with the child.

Seeing social entrepreneurship woven throughout Hillbrook's curriculum was a deeply affirming moment for us too – it confirmed what we have always believed: that children are capable of exactly this kind of thinking, and that it is our job to give them the conditions in which to do it.

Abby Kirchner and Melissa Groff at Khan Lab School.

That conviction carried us to Khan Lab School, where we felt immediately at home. We moved through open learning spaces and observed middle school Socratic discussions — the kind where students are doing the intellectual heavy lifting, not waiting to be told what to think. We reviewed mastery-based transcripts, spoke with their college counselor, and had conversations with educators about the mechanics of mastery-based learning and what it looks like across grade levels. What struck us most was how clearly the philosophy we had been articulating in our own design conversations was alive and functioning here — not as an experiment, but as an established, practiced reality.

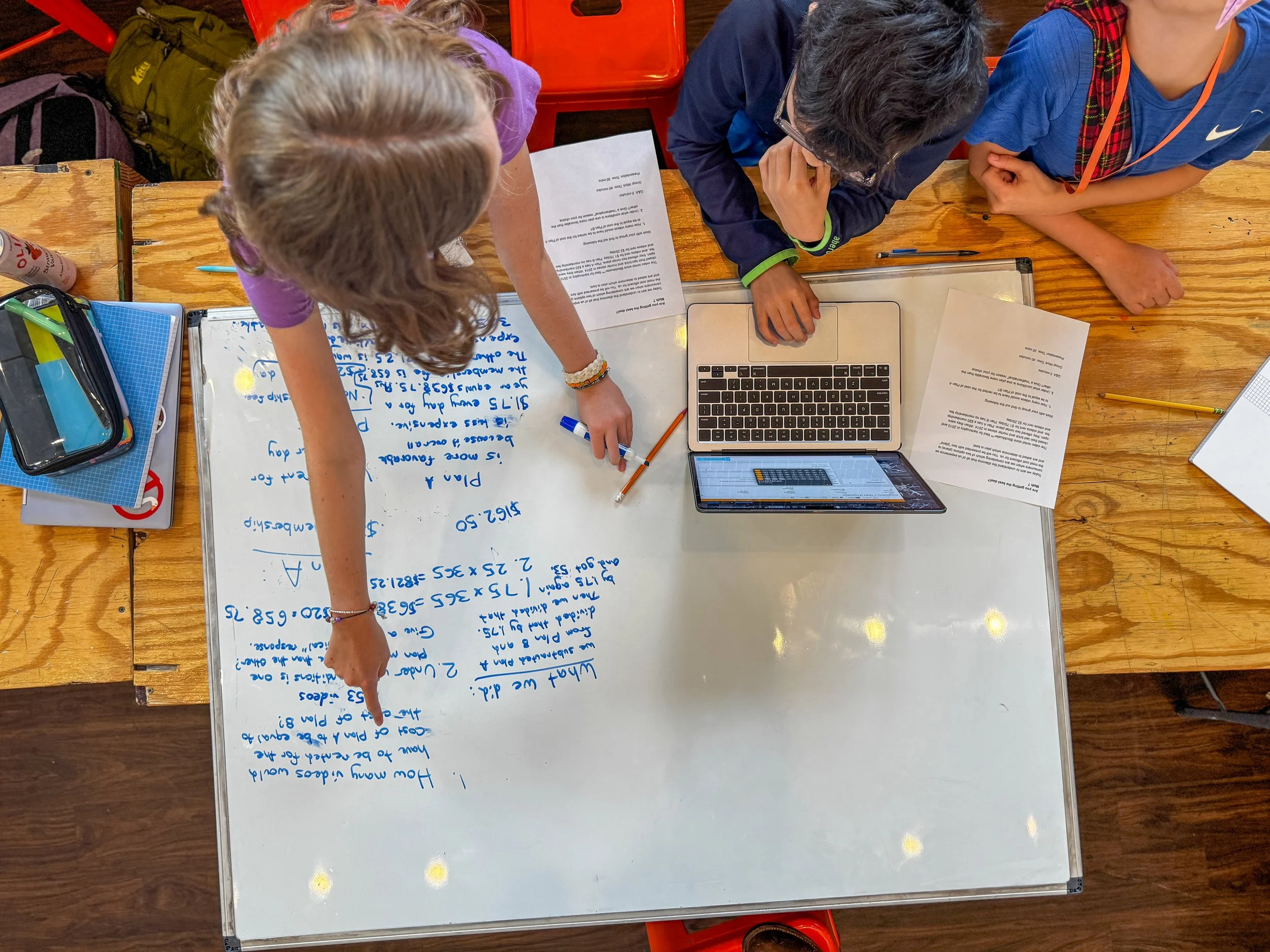

Visiting The Nueva School's Upper School campus was, in a word, exhilarating. Nueva's resources are in a different category from those of most schools — Stone included. And yet, at the heart of everything we saw was the same skills-based philosophy our Middle and Upper School students experience every day. We found ourselves in the same conversations: the tension between mastery-based learning and traditional grading, the question of what it actually means to know something, the difference between covering material and building understanding. It was here, too, that our thinking crystallized about how we can amplify the weeks-long Quests elementary students at Solvit are already doing, and it was when some of our key tenets for Lower School Enrichment Week (a younger version of the current Middle School/Upper School “Intensives Week”) solidified.

Enrichment Week is a “deep dive” week, a dedicated period when we will set aside the typical daily schedule to pursue deep, collaborative projects within the Stone and Lancaster communities — something we already do with great success in Middle and Upper School, and something we are now ready to bring to our youngest learners. The case for it is straightforward: concentrated focus creates the conditions for real mastery in ways that a standard weekly schedule simply cannot. That depth of immersion produces a state of flow and mirrors how meaningful professional work actually gets done.

Some projects should be place-based — learning about sustainable farming at a local Lancaster farm, exploring urban planning at Penn Square, designing a restaurant experience for parents — making the curriculum "sticky" in a way that shapes how students approach future learning long after the week is over.

The thesis we return to — rigor and joy are not in opposition.

Skills like interviewing local business owners or presenting to professional audiences will amplify the confidence our Lower School students already, impressively, possess. And perhaps most importantly, deep dives build the executive functioning, goal-directed persistence, and social-emotional capacity — including conflict management and collaborative problem-solving — that we want students to carry with them for life. The brain, we know, stays open to a problem during unstructured time. That is where the best "aha" moments tend to live.

Our conversations in California were not abstract. They were the working questions of educators who take seriously what school is for — and they sharpened our own thinking considerably.

The thesis we kept returning to — the one we continue to defend — is this: schools are fully capable of teaching foundations, iteration, and play at once. Rigor and joy are not in opposition. Depth and creativity are not in tension.

And yet too many schools are still in the business of ranking the potential of our children rather than developing it.

Developing our students’ relationship to work and growing their imaginations is urgent. For example, in the past five days, I have encountered four separate published essays about AI's impact on the future job market — not counting the two a parent in our community sent me, and not counting the two podcast episodes that appeared in my daily feed.

The message running through all of them was the same: the students we are mentoring today will be competing with intelligent machines, and the edge they will need is not more information.

It is judgment.

It is creativity.

It is the capacity to ask a question no one has thought to ask yet.

Those are not soft skills. They are the whole point of education.